This post started out as a Bob and Ray video clip.

This post started out as a Bob and Ray video clip.

It’s an entertaining segment in which Messrs. Elliott and Goulding have a chat with Dick Cavett about two comedy heroes shared by all three men – Robert Benchley (in the white suit) and Fred Allen. The discussion is followed by a terrific Wally Ballou interview with one of Bob and Ray’s lesser-known characters, Mr. Wwqlcw.

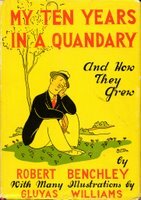

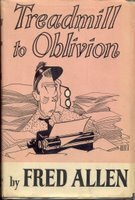

Watching this clip sent me back to my Benchley books. My White Suit is a piece collected in My Ten Years In A Quandary And How They Grew (1936). I also pulled Fred Allen’s Treadmill to Oblivion (1956) off the shelf and started reading bits and pieces at random. This led me to change my mind about… well, I don’t want to get ahead of myself. First, enjoy the clip:

Benchley’s short film That Inferior Feeling (1940) is all about feeling ill at ease in situations where there are no real reasons to feel ill at ease. And despite the promises of the ask-your-doctor ads, no amount of Paxil or Prozac will alter the clothing-purchase experience for those who find it painful.

There are still many men who experience great relief each time they exit a store without being  detained for shoplifting. Not because they have actually committed that heinous act, but rather because they sense in themselves an inability to appear nonchalant or non-suspicious looking as they meander toward the egress.

detained for shoplifting. Not because they have actually committed that heinous act, but rather because they sense in themselves an inability to appear nonchalant or non-suspicious looking as they meander toward the egress.

Those of us who admire entertainers of yesteryear often have a tendency to drift along with the undercurrent of melancholy that is the wake of the public’s fickleness in its never-ending search for new amusements. Younger fans who missed the heydays of their idols often make substantial efforts to seek out the portion of the work that survives, then use it to proselytize on behalf of their hero. They shake their heads sadly when few join them in their celebration of those who reached incredible heights of popularity in their own day… only to arrive at a near-total indifference and anonymity in ours.

Ray Goulding can’t understand why they don’t show Benchley’s short films on TV. Dick Cavett correctly believes that Benchley will be “…virtually unknown to the younger listener or viewer,” and suggests a trip to the library. Cavett’s bittersweet story about Fred Allen’s “fan club” portrays the radio star as an under-appreciated, nearly forgotten man at the end of his life.

Ray Goulding can’t understand why they don’t show Benchley’s short films on TV. Dick Cavett correctly believes that Benchley will be “…virtually unknown to the younger listener or viewer,” and suggests a trip to the library. Cavett’s bittersweet story about Fred Allen’s “fan club” portrays the radio star as an under-appreciated, nearly forgotten man at the end of his life.

Hero worship can be equal parts adulation and sympathy. Adulation and sympathy not just for the hero, whose greatness was once – but is not currently – recognized; but also adulation and sympathy for one’s self, as a person both blessed and cursed with the capability to perceive and champion criminally overlooked genius.

Yet Allen, for one, expected his fate. He finishes his 1954 book Treadmill To Oblivion with these words:

Yet Allen, for one, expected his fate. He finishes his 1954 book Treadmill To Oblivion with these words:

Whether he knows it or not, the comedian is on a treadmill to oblivion. When a radio comedian’s program is finally finished it slinks down Memory Lane into the limbo of yesteryear’s happy hours. All the comedian has to show for his years of work and aggravation is the echo of forgotten laughter.

Like Benchley’s man in a white suit who can’t help feeling ill at ease in non-threatening situations… like the law-abiding citizen worried about the security guard’s suspicions… there’s no good reason to feel bad for comedians and other successful entertainers who connected strongly with the audience of their day but are now largely forgotten. Neither should we feel sorry for those who can’t, today, appreciate an old Fred Allen radio show or Robert Benchley short. Few can. And we should never, under any circumstances, make it our mission to convert the heathens who will not acknowledge, let alone bow down before, the old gods some of us still worship.

Because truth be told, the treadmill never actually reaches oblivion. As in Zeno’s paradox, there’s always another halfway point ahead, a halfway point where fewer remember, fewer enjoy, fewer care.

Between 1932 and 1949, Fred Allen built up an average speed on that treadmill. As soon as he got off, that average speed started to decline. But it never quite reaches zero.

Did you ever hear of the movie Fickle Fortune?

Did you ever hear of the movie Fickle Fortune?

From the New York Times, November 16, 1997:

From the New York Times, November 16, 1997: